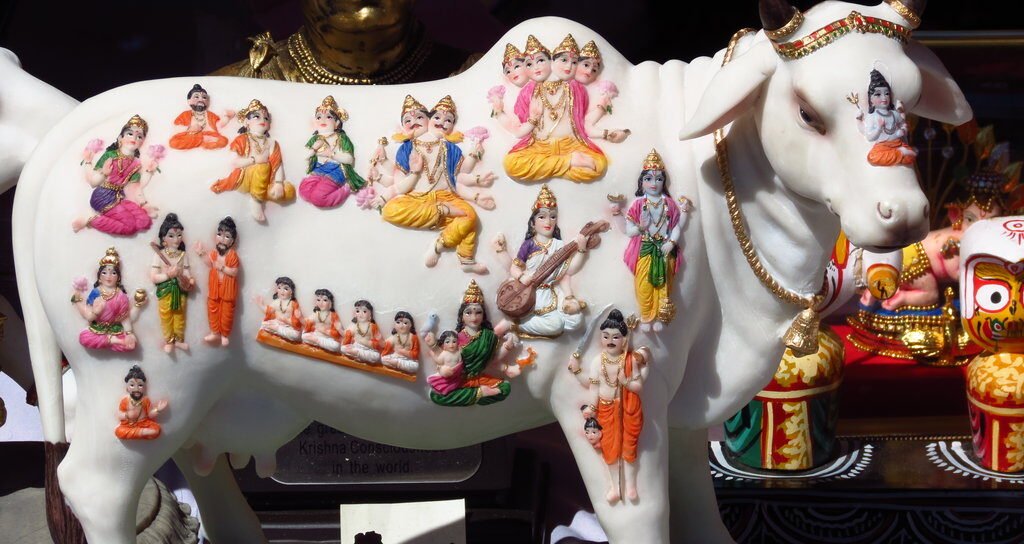

At Jaipur’s Vidyadhar Nagar Stadium this week, the organisers of the “Gau Mahakumbh”—billed as a cow-based global summit and exhibition—promised technology, sustainability and commerce: 200–350 exhibitors, dairy machinery, organic inputs, “gaushala” management. What the crowds also got, and what The Wire’s on-ground report captured with crystalline clarity, was something more telling about the temper of our times: the confident sale of bottled gaumutra (cow urine) as a cure for disease, wrapped in a rhetoric that fuses commerce, faith and politics.

At a stall run by the Gayatri Parivar Gaushala Samiti, Pradeep Gupta, a 55-year-old advocate from Kota and a self-described Hindutva supporter, displayed a neat line of plastic bottles “for different ailments.” When a visitor asked about a remedy for a fatty liver, Gupta reached for one and said, in essence: this is what you need. Elsewhere at the exhibition, the promise widened—to cancer, to infections, to the vaguer terrain of “immunity.” On social media, Rajasthan’s education minister Madan Dilawar was shown visiting and inaugurating the event. The mise-en-scène was pure 2025: a public fair dressed as a developmental expo, political optics folded into devotional economy, and the old faith-heals pitch presented as if it were self-evident truth.

What does the evidence say? Not what the bottles claim.

There is a scattered pre-clinical literature—cell lines and animal work—suggesting that cow-urine distillate may act as an antimicrobial or a “bio-enhancer” with certain drugs. One oft-cited experiment reported that a distillate appeared to potentiate paclitaxel in a cancer cell line. Interesting, yes. Clinically meaningful? Not yet. These are mechanistic or laboratory studies, not trials in human beings with real disease and real outcomes. On non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), India’s AYUSH establishment has funded research and even listed a double-blind trial evaluating an AYUSH formulation; but results that meet the threshold of modern clinical evidence have not been published in major peer-reviewed journals. Reviews in Ayurveda-focused publications sometimes mention gomutra with Triphala for NAFLD, but these are compilations of hypotheses and small, low-quality studies. They call for proper trials. They do not constitute proof.

This distinction matters. The leap from in vitro or animal models to human therapy is not a formality; it is the crux. Most putative “bio-enhancers” die on the hard anvil of clinical testing. To pretend otherwise—by handing a bottle across a counter and implying cure—is to erase the line between hope and harm. Liver disease is an unforgiving teacher: delay effective care, and fibrosis does not wait. Worse, “natural” is not a synonym for “safe.” Herbal-induced liver injury is a documented phenomenon. A product that does nothing is one kind of problem; a product that quietly injures is another.

Nor is this simply a scientific quarrel. It is a regulatory one. India has clear, if imperfectly enforced, rules. If you sell an Ayurveda āhāra (a food) you come under the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India’s 2022 framework and may not make disease-cure claims. If you sell a medicinal product, you fall under the Drugs & Cosmetics Rules for Ayurveda, Siddha and Unani (ASU) drugs: you need a licence, GMP compliance, and you cannot hawk “cures” for specified diseases without meeting additional thresholds. The Union Health Ministry has already warned vendors who slap FSSAI numbers on cow-urine concoctions and then market them as treatments. These are not semantic niceties. They separate consumer choice from consumer fraud.

Which brings us back to the Gau Mahakumbh. No one disputes the right of citizens to practice and cherish their faith, or of gaushalas to seek sustainability, or of researchers to interrogate traditional pharmacopeia with modern tools. What is indefensible is the slippage we witnessed in Jaipur: a government-blessed fair (a minister cutting ribbons), a stall making disease-cure pitches, and bottles exchanged as if clinical evidence had been litigated and won. The state cannot be neutral about this. When public officials visit, they confer legitimacy. When regulators look away, they convert a grey zone into a green one.

The defence is predictable: that gaumutra has been used for centuries; that AYUSH systems have their own epistemologies; that Western journals are gatekeepers of a hostile canon. But none of these arguments justifies bypassing the basic ethic of medicine: claims of cure require proof. India’s classical medical traditions deserve better than to be reduced to fairground transactions and WhatsApp pharmacology. The honest path is slower but surer: standardise preparations; register protocols; run adequately powered, ethically approved trials with transparent endpoints; publish the results wherever the methods and data can stand scrutiny; label products accurately; and police the marketplace against quackery that hides behind culture.

There is also a political economy here that we prefer not to see. The cow is not simply an animal in the Hindutva imagination; it is a totem through which power is expressed and wealth is mobilised. The “cow economy”—from artisanal dung products to ayur-adjacent wellness—has become a retail front for a larger ideological project that treats skepticism as sacrilege and regulation as obstruction. The Jaipur exhibition put this on stage: a devotional marketplace that asks to be treated as science while claiming immunity from scientific tests. It wants public money, official presence and legal indulgence; it does not want the burdens that accompany any of the three.

Consumers, meanwhile, are left to navigate a thicket of labels and lore. Here the guidance must be simple and firm. If you are evaluating such products, check the packaging: is it a food with an FSSAI mark making nutrition claims, or a licensed ASU medicine? Are there curative claims for cancer, liver disease, diabetes? If yes, walk away. If you wish to explore an AYUSH intervention, do it with a qualified practitioner who will coordinate with your treating physician, especially for liver disease where drug-herb interactions can be consequential. And demand what the marketplace refuses to supply: evidence you can read, not anecdotes you must believe.

What happened at the Gau Mahakumbh is reportage, not endorsement. A journalist observed a stallholder promise a bottle for a fatty liver and recorded the exchange. The health system’s duty begins where the stall’s flourish ends. When belief crosses into the territory of cure, the state must insist on the discipline of proof. And when ministers lend their presence to events where cure-claims are commonplace, they must also lend their authority to the one message that actually saves lives: there is, as of today, no high-quality clinical evidence that drinking cow urine cures fatty liver or cancer.

The cow does not need pseudoscience to be revered. But patients do need truth to be treated.